Overview

To begin with, this is probably the most difficult book I’ve ever read. It’s extremely academic and required note-taking to understand. If you decide to read Capital, keep that in mind. Nevertheless, it’s intriguing, well-thought-out (it took fifteen years to write) and somewhat provocative.

We all have heard about the dangers of skyrocketing income and wealth inequality, especially during the recent presidential election. In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, French economist Thomas Piketty, arguably the world’s leading expert on income and wealth inequality, sets out to explore the dynamics that drive the accumulation and distribution of capital and how inequality, investment, growth, debt, politics, and more are affected. The book studies capital from the 1700s to the present and makes predictions about its role in the twenty-first century.

“Capital is never quiet: it is always risk-oriented and entrepreneurial, at least at its inception, yet it always tends to transform itself into rents as it accumulates in large enough amounts – that is its vocation, its logical destination.” –Capital in the Twenty-First Century, pg. 185

Capitalism’s Contradiction: r > g

In the long run, r, the rate of return on capital, will be higher than g, the rate of growth of income and output. This is a historical fact, not a logical necessity. It implies that wealth accumulated in the past grows more rapidly than output and wages. Entrepreneurs inevitably become rentiers, exploiting their capital to the detriment of society, making them more dominant over those who own nothing but their labor. “The past devours the future,” says Piketty.

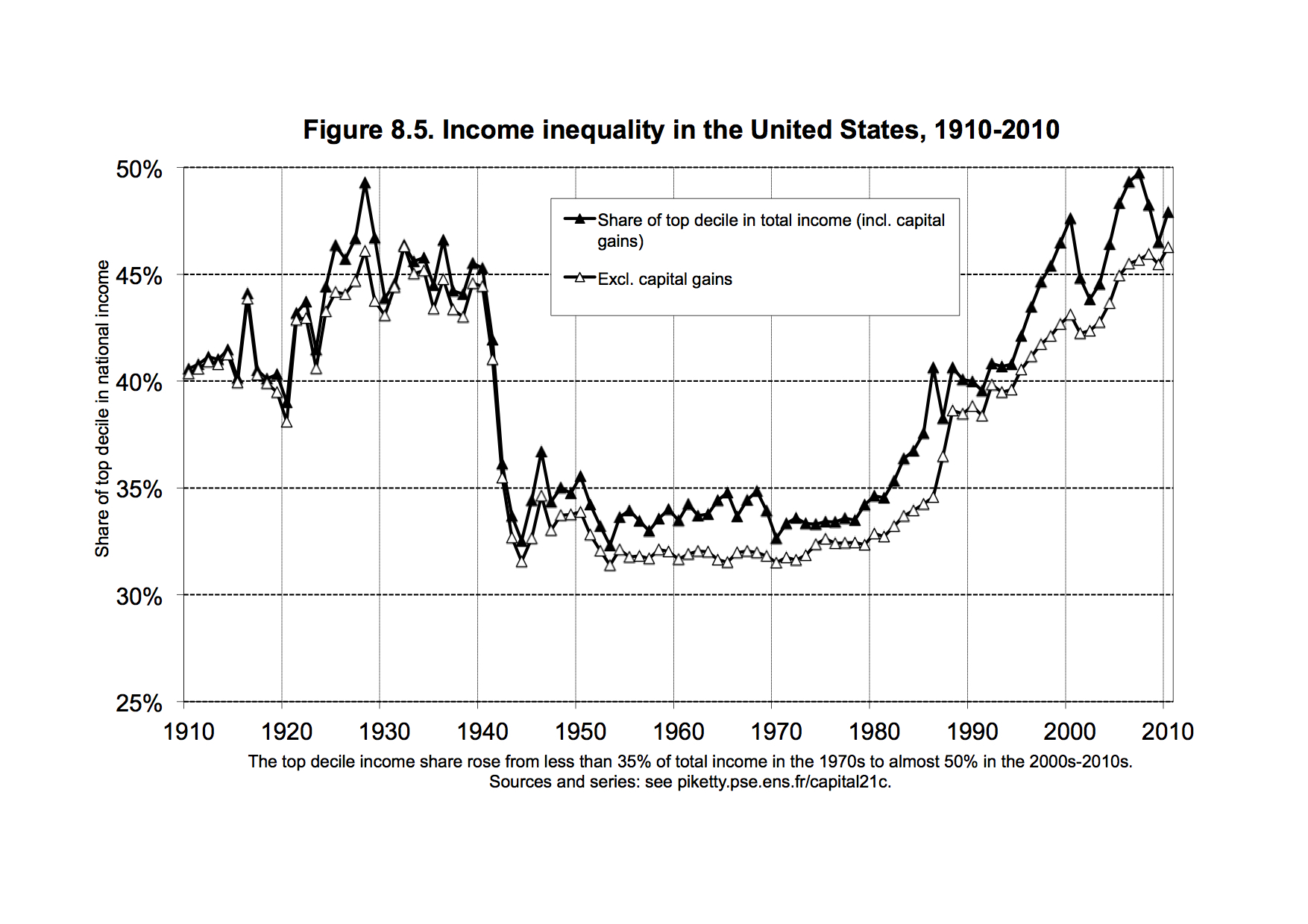

The Great Depression and World War Two, combined with new economic policies, compressed inequality and gave birth to what economist Paul Krugman nostalgically calls “the America we knew and loved.” America experienced massive growth (the elusive 4%), and we thought we had overcome capitalism’s contradiction. But, we were wrong.

One way to reduce inequality is to increase growth, including demographic growth, but Piketty demonstrates that 4% growth was a historical anomaly that we shouldn’t expect anytime soon. Economic growth on the magnitude of 1% to 1.5% is historically average and quite good in the long run, assuming the growth is shared equitably.

Regulating Capital in the 21st Century With a Global Tax on Capital

Regulating Capital in the 21st Century With a Global Tax on Capital

This is where things become “provocative,” or as provocative as the topic of political economy can be. Piketty makes several recommendations, including a significantly higher top marginal tax rate (80% for the richest citizens), but it is a global tax on capital that is the most unique.

“But if democracy is to regain control over the globalized financial capitalism of this century, it must also invent new tools, adapted to today’s challenges.” –Capital in the Twenty-First Century, pg. 515

A global tax on capital would be progressive and include all kinds of assets: real estate, financial assets, and business assets – no exceptions. The tax rate would be low (between .1% and 2%, perhaps), and hardly affect an average citizen. The primary purpose of this tax is not to finance the social state (i.e. public investments in education, healthcare, infrastructure, etc.), but to regulate capitalism. It would promote democratic and financial transparency with data sharing by banks, including those in so-called “tax havens,” which thrive on secrecy. It is worth noting that tax havens have nothing to do with the principles of a free market economy.

“No one has the right to set his own tax rates. It is not right for individuals to grow wealthy from free trade and economic integration only to rake off the profits at the expense of their neighbors. That is outright theft.” –Capital in the Twenty-First Century, pg. 522

The global tax on capital will provide an incentive for individuals to invest in better investments (ones with higher returns) while relying on the forces of private property and competition. It is the most appropriate response to capitalism’s contradiction, r > g, and will be most adept at reducing inequality. Clearly, this is a utopian idea that is unlikely to be implemented in the near future.

My Recommendation

Capital is a lot to get through. This is my longest blog post and I barely scratched the surface of the work, if that is any indication of its density. It’s valuable and wonkish, and if you are passionate about economics, politics, or finance, this book is for you. Otherwise, I recommend reading shorter, more digestible books on inequality, such as Robert Reich’s Saving Capitalism: For the Many, Not the Few.

Get your copy of Capital in the Twenty-First Century